The 1952

Monte Carlo Rally

with

Bo Boesen, Göran Norlander

and

Jowett Javelin.

Written by Göran Norlander

In January 2002

©

Göran Norlander.

FOREWORD

A 50 year Jubilee.

Our friends Anne and Tony Dawson from Otley near Bradford visited us last summer. Tony and I spoke much about our common interest, cars and motorcycles, and of course I told him about the rallies I made in the early 50s, with my friend Bo Boesen in a Jowett Javelin. Coming home, Tony made me a member of the Jowett Car Club of whose existence I was unaware until then. Their librarian, Noel Stokoe, wrote me and asked if I had any pictures from our rallies. I sent him what I have, and so did Bosse.

Whilst searching for these pictures, my old scrap book from 1952 showed up, and many things came back, that I had long forgotten. There was an article that I wrote 1952 for the internal company paper, where I was employed. The scrapbook plus Bosse’s remarkably good memory inspired me to write down the whole story.

We started from Stockholm on 22nd of January 1952

- exactly 50 years ago.

Göran Norlander

Fleurines January 2002.

It was a tough rally that we almost won, but let me tell the whole story.

At this time it was still possible to participate in The Great Rally as amateurs and with reasonable means. Most of the competitors were of this category like ourselves. My close friend Bo Boesen, called Bosse, being a well-known photographer in Stockholm is a motor enthusiast as myself, and the background to our participating in the 1952 Monte Carlo Rally started about two years earlier.

In 1949 I had finished my studies in USA and in Stockholm, and as a young engineer speaking good English and German, but a poor French, I felt that I had to learn my mother’s tongue better. So I left for Paris in my 1936 Dodge, with a 6 cylinder side valve motor of about 60 Hp in a very heavy car. I found a small job in a company importing machinery and tools from the US, partially supported by the Marshal-plan.

Then, as now, very few French spoke any foreign language, so my engineering knowledge plus English came in very handy. But first I had to learn some French. I was placed in the warehouse as some junior worker. My very first job as an engineer was to open the crates coming in, straighten the nails and stack them according to size. At this time, 4 years after the war, there was still a lack of many things, and nothing was wasted.

After some time I was sent out to give instructions how to operate a delivered lathe or milling machine, which I did with the American handbook in one hand. These assignments took me and the Dodge out to all corners of France. In January 1950 a large automatic machine to produce drills had to be assembled in factory situated in a small town, Pont de Beauvoisin near Grenoble. I was sent there to give a hand with this job that went on for 3 winter months.

My eldest sister was not very healthy, and her doctor had prescribed her to spend the winter in a warmer place than Sweden, and she rented a flat in Cannes that year. Every weekend I went there, about 500 km across the Alps Maritimes, following the classic Route Napoléon, Grenoble – Gap - Digne – Grasse, which is also used for the Monte Carlo Rally! The attraction to go to Cannes was not only my sister, but also her very cute neighbour.

This winter was, as most winters at this time, cold and with lots of snow. Driving across those Alps was not easy, and sometimes even hazardous. A good help was an information office, le Syndicat d’Initiative, in Grenoble. I always stopped by there and got the latest information about the snow and road conditions, and sometimes I had to put on the snow-chains immediately, and sometimes I had to take another and longer road to get South.

This mountain road was in very bad shape after the war. Hardly any protections on the valley side remained, and the road was sometimes very narrow. The only communications to the mountain villages was by bus or car. Also some trucks trafficked the Route Napoléon. All these heavier vehicles had very strong horns that they used before every curve, and there are quite a few. When hearing a horn blew it was best to stop the car as close as possible to the road edge, and wait for the bus or truck to pass. After a few weekends I mounted one of these horns on my car, and then when passing the bends other automobiles were giving me free passage.

When the spring finally came, I knew Route Napoléon by heart, and also driving that somewhat clumsy car with an under-dimensioned engine, gave me a particular skill that I believe no normal training could achieve.

Next winter in January 1951 Bosse made the Monte Carlo Rally in a Dyna Panhard, belonging to Arne Hemingsson

In the coming spring Bosse asked me if I wanted to make the Swedish Midnight Sun Rally with him in his Fiat 1400, and of course, no objections. That rally was almost as long as the Monte Carlo, but ending way up North in Kiruna, the most northern town in Sweden far above the Polar Circle.

In between those big rallies, we also took part in some local courses with various friends.

In the autumn 1951 we decided to make the next year’s Monte Carlo Rally with my new Jowett Javelin. We knew from our experiences that a number of minor changes had to be made to the car, in order to face all difficulties that might occur when driving over 3,300 km (2050 mi) in winter conditions.

The Jowett was then new on the Swedish market, and we found it to be a very good car for cruising. It’s 1.5ltr, 4 cylinder boxer-engine, was not very powerful, and the car could not be considered as fast, but it was very easy to drive with good visibility. The road holding was excellent for its time, basic criterior for a rally-car. Sweden still had left hand traffic, and consequently my car had the steering wheel on the right side.

North of Stockholm is an area with a number of small curvy and hilly roads with sand pavements, where we used to drive around to test various equipment.

We learnt the hard way, that the weak part on the Jowett was the rod bearings in the engine. One of the reasons for this might have been difficulties in maintaining an acceptable oil temperature at hard driving. The short boxer motor gave proportionally a smaller cooling surface for the oil, compared to a straight engine. Anyway that was my theory. To prevent this I installed, in tandem with the oil filter, a Volkswagen oil cooler. This cooler was mounted on top of the motor just behind the grill. This also increased the oil volume, which was good for this engine. Thanks to this cooler we saved the engine at an incident during the race.

The carburettors have a ring to balance the petrol injection with the air velocity controlled by the throttle, a sort of venturi. In mounting one size larger rings we made the motor more “lively” which is important in alpine driving using quick toe and heel gear-shifting in the hair pin bends. Also the acceleration was improved. These larger rings did not add any more power, and the idling revs had to be increased. I believe that the petrol consumption suffered, but that was of less importance.

We had 4 spare spark plugs with the corresponding key mounted in a bracket under the hood for quick changes.

The start in Stockholm, January 22nd, 1952, at 16h40.

Already at the start in Stockholm the temperature was far below zero, and we had a radiator screen that could be opened more or less to maintain a constant water temperature.

One item that we spent much time on was the head lights. In snow, fog or heavy rain, the visibility is reduced by the headlights reflecting some light vertically, thus lightening up the snow or fog near your eyes. We made, in aluminium, shades like on a peak hat, that were fixed to each headlight. They were about 200 mm (8”) long. The undersides were painted in matt black, to avoid reflections down on the snow that in return throw the light back and up.

Fog lights were also very important. I remember that we borrowed several models, and one foggy evening we went out and parked alongside a wooden fence. Then connecting one light after the other, beaming them parallel to the fence, and then we counted from the inside of the car the number of visible ribs in the fence. One of the lights had an orange colour. This one was outstanding, but it was doubtful if that colour on a front light was legal. Anyway, we mounted it together with 2 ordinary Marshall fog lights. Later during the rally, we definitely found this light superior to the others also in heavy snowfall.

A roof mounted spot light that could be operated from the inside, was of great help. It was not only used for reading road signs, but also for guiding the man at the wheel. The co-driver pointed the beam into the curves before arriving there, and then followed the bend until the car was out on straight road again. This was of very good help at night time in the mountain serpentines.

Snow tires were of outmost importance, and from other courses we had experienced a Finish tire called Wittmer. Those had a thick layer of rubber with squared or rectangular points, roughly 1 to 2in. sides. They gave an excellent grip in snow, but of course less on ice. Snow chains are good for snow and low speed. We wanted something better, so we started to experiment, which led to an original snow chain mounted on the front wheels.

We mounted a Wittmer tire with its hub in a turret. A grove was cut in the centre line of the tire about ¾“ wide and ½“ deep. Then we emptied the tire of air and forced a motorcycle chain with the exact length as the tire circumference into the grove. After that, the tire was pumped up to about 3 Bars (or about 50% more than normal), and the chain was securely fixed to the tire centre line and sticking up a little above the rubber surface.

The result was that when braking hard all 4 wheels locked, but the chains on the front wheels functioned as skates and we could still steer the car. Thanks to this, during the snow part of the rally, we could go faster and more safely through the curves than our competitors.

The steering-chains on the front-wheels were very efficient.

We brought with us in the trunk, 2 spare wheels with mounted steering chains, and also 2 jacks and suitable wrenches. We practiced fast front wheel changes, and finally we could carry out this operation in 1½ minutes from when we stopped the car until we started again.

In the 1953 Monte Carlo Rally, many cars appeared with such steering chains, but then there were no snow.

Finally we installed an extra petrol tank of about 60 L (13 UK gallons) in the trunk towards its front wall. This tank was connected by a valve to the normal petrol pipe. These 60 extra litres made us less dependent of re-fuelling, especially when short of time.

The backseat served as bunk for a nap now and then. It was not very comfortable, as it had to be shared with some luggage. Among other things, we had to bring our tuxedos for the final banquet.

In January 1952 we were ready, and on the 22nd at 1640hr we started on the big adventure from Stockholm.

39 cars started from the Swedish capital, 21 Swedes, 11 Finns, 4 Danes, 1 Norwegian, 1 Dutch and 1 French! Numbers 148 to 189, 2 did not come to start, and we were in the end of the line with number 186.

In winter it is already dark at this hour in Stockholm, and it was bitterly cold, as I remember, 15 to 20°C below freezing point (0°F) and of course snow. The Swedish roads were well cleared from snow and it was a fairly easy driving south. 50 km/h (31 mph) was the stipulated minimum average speed between control points, including service stops. This was easy to respect under normal conditions, but when trouble showed up the time ran away very quickly. Every minute’s delay gave 10 penalty points . More than 2 hours accumulated delay was equal to disqualification. The average maximum speed allowed was 65 km/h (40 mi/h).

Already after about 200 km (125 mi) our engine started to run uneven, gave less and less power, and finally it stopped. It started again at first try and ran well for a while, but the procedure was repeated. We were searching the cause, but found nothing wrong with sparks, fuel supply etc.. We managed to reach the first checkpoint in Huskvarna, about 330 km (205 m) from the start. Somebody there mentioned that maybe the carburettors were freezing. We were not allowed to do any repairs, or even to open the bonnet in the control point area. But as soon as we were on the road again, we stopped and wrapped up the 2 carburettors in a daily newspaper, and after that we had no more trouble of that kind. My guess is that ice was formed after the venturi inside the carburettor, blocking the nozzle, and as soon as the motor stopped, the heat radiated from the motor cleared the passage.

We continued over Helsingborg by ferry, about 20 minutes crossing to Denmark. At this time there were speed restrictions all over that country, and max velocity allowed was 60 km/h (37 mph). It seemed to us as though the entire Danish police-force were out that night, and everybody was driving very correctly.

Now the next engine trouble showed up, a valve got stuck! What to do? Then we remembered a bottle of Redex that somebody gave us before the start. A “wonder elixir” to mix with the petrol to get a smooth running and inside-clean motor. Why not try it! In the middle of the night we stopped in a small square in Copenhagen, no traffic and people sleeping in their beds. We took the air filters off and poured the liquid directly into the carburettors with the motor running at fairly high revs. There was no wind and a fantastic smoke was produced and the entire square disappeared in a heavy dark cloud. The valve loosened and we quickly put the filters back and disappeared before the fire-brigade showed up. We concluded that Redex, after all, must be a good product!

The next stop was Korsör 110 km (68 m) from Copenhagen. There we had to take another ferry across the Great Belt to Nyborg on the Danish island of Fyn. The crossing takes about 1½ h, and there was a boat only every hour. Nobody wanted to miss the scheduled one, and there was also a risk that it should be no place left on the ferry. This caused everybody to increase their speed to arrive first at the ship, and near the harbour we were all racing. As far as I know, the police caught only one Swedish driver for speeding. Everybody came onboard in time.

As soon as we were onboard I went to the lounge and found an armchair where I immediately fell asleep. Disturbed by some noise from the ship moorings I woke up and thought we were in Nyborg, and rushed down to the car deck – but we were still in Korsör! After that I could not sleep any more on that crossing.

Bosse and I shared everything (except the long-legged, 2-cylinder models). The costs, including the entrance fee, and also the time at the wheel were equally split up. Every 2 or 3 hours we shifted. The co-driver’s duties were several. A part of the navigation, at difficult conditions, he should also lead the driver by indicating verbally what the road ahead looked like:. For instance; “sharp curve ahead, then straight 100 meters. Snow in bend etc..” When dark he also had to follow with the roof spotlight. As we had steering-wheel on the right side, he also had to tell if road was clear before overtaking another car. Only during easy driving he could take a nap in the back seat.

After Nyborg we crossed Odense, where H.C. Andersen used to live and wrote his wonderful tales. Another slow 200 km (125 mi) brought us to the German border, and it was a sort of relief not to have to watch the speedometer all the time anymore.

Outside Hamburg we were met by a motorcycle police waiting for us. He escorted us through the city. Full speed, and we could hardly follow him at 120 km/h (75 mi/h) . In every street crossing there were other officers stopping the traffic. Here and there people were crowding to see “the big show”!

There were no motorways in Europe at this time, except for a few in Italy and Germany. The very first was built by Fiat from Turino to Milano, to test their cars, and Hitler copied the principals from this autostrada and built his first autobahn from Hamburg to Bremen, 120 km (75 mi). We followed this road that was not yet completely repaired from war damages. Many bridges were temporary one-line military steel constructions.

After Hamburg we got troubles again. This time it was the left front wheel bearing that started to make noise. How could we solve this new problem? We did not have that bearing with us nor the special tools needed. We must get external help. In Germany we could not expect a repair shop to have English inch-tools, nor a suitable bearing. Arriving to the checkpoint in Hengelo, at the German-Dutch border, we called at 11 o’clock in the evening the Jowett representative in Amsterdam, that was keeping night watch.

It was snowing and we were in a hurry to make up spare time. He met us, 3h30, just before the checkpoint in Amsterdam, we were then 45 minutes ahead of the schedule. He guided us to his workshop where the doors were opened, and we hardly had time to stop the motor, before the car was being lifted up. All tools and parts for a wheel bearing repair were placed on a white cloth, and 4 men attacked the car. Some overlooked various things while the bearing was changed. When the wheel was back we discovered that the inner rubber gasket that prevents grease to come into the brake drum was still on the table! A number of words “impossible to translate” in Dutch and Swedish were loudly expressed.

We rushed to get our road book stamped in the control that fortunately was close to the Jowett garage and we arrived 3 minutes before the time limit. Then back to the work shop, wheel and bearing off, gasket in and final assembly. 45 minutes delayed we were on the road again towards Brussels. The Owner declared generously, with big gestures, that the whole operation was on the house. All this passed during the night, why no traffic problems occurred.

We succeeded in making up the lost time, partially thanks to a dedicated motorcycle police in La Haye. Like his college in Hamburg he guided us through the town with full throttle. His motorcycle had a side car and I can still see how this lifted in the right turns. After Brussels we continued across the Ardennes to Reims in France. We passed the wonderful little town Dinant in a steep valley near the border, where we saw the very high chimney that became famous during the last war. RAF pilots on missions towards Eastern France or Southern Germany, and when flying very low, used this chimney as land mark.

At every checkpoint the local club offered coffee or soft drinks, sandwiches, and sometimes a local souvenir. In Reims, the capital of the Champagne district, offered Champagne as much as you could drink while waiting to start again. No food! And as we were tired one glass was enough. Our Finnish friends, however, accepted gladly the kind offer from the Reims Automobile Club. Shortly after on our way to Paris we saw their car, an Austin if I remember right, as a wreck way out in a field. Bosse and I thought that we had seen them for the last time.

In Paris the checkpoint was in the magnificent French Automobile Club localities, and to get there we strolled along the Champs Elyssées like any tourist. From there we continued to Bourges.

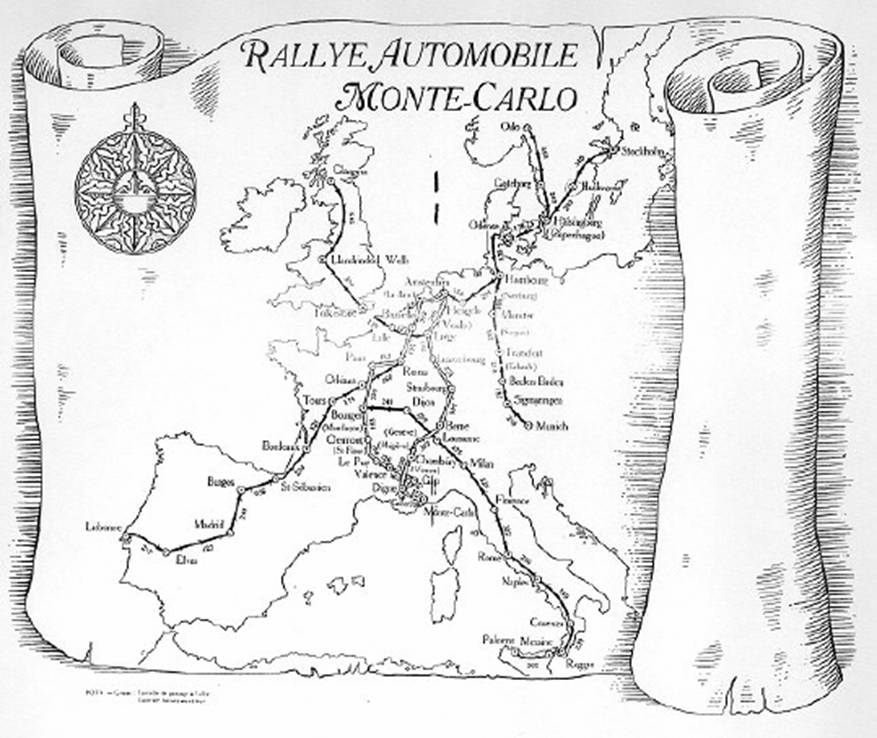

One of the Monte Carlo Rally principals was to assemble competitors from all corners of Europe. When leaving Stockholm we met the drivers from Oslo in Hälsingborg, and in Hamburg the Germans from Munich showed up. In Amsterdam the people coming from Monte Carlo and also Glasgow joined us, and from Reims the automobiles starting in Lisbon used the same road. Finally in Bourges the Italians showed up coming from Palermo in Sicily. Then all of us had made more or less the same distance from start, and the most difficult part of the rally-road ahead became common, across the Massive Centrale and Alpes Maritimes. To avoid crowding on the roads and in the checkpoints, starting times were spread out. We had the Oslo drivers behind us, and before the Swedish group were the English.

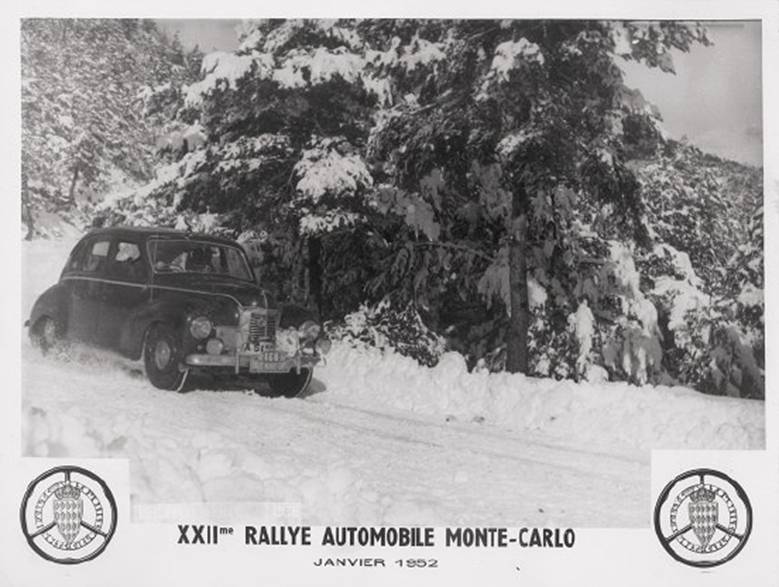

Next control point was Clermont Ferrand, and on this way it started to snow heavily. We switched to our front wheels with steering chains and arrived in time to Clermont. On the way to the next stop in Le Puy, it started to be very difficult driving,

After Le Puy we headed on the shortest road to Valence, but after a while, as there were no other cars on this way we understood that something was wrong. A man along the road side explained that this road was blocked further up. It seemed that other drivers had been informed about this in the Le Puy checkpoint, except for us and a couple of other Swedish drivers. We turned around and took a longer road towards Valence. It was snowing very much, and the road was very curvy, and as we caught up with the others, we were also delayed by difficulties in over-taking other cars. How many we saw off the road or stuck in snow walls that night, we did not have time to count. We could not make up all the time we lost in choosing the blocked road, and we arrived to Valence 8 minutes delayed, which gave us 80 points penalty, and there was nothing we could do about that.

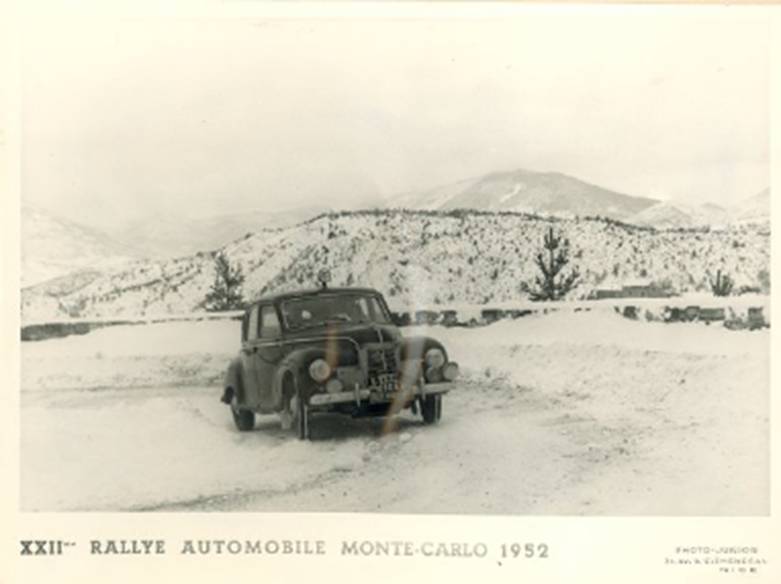

Now all our preparations we had done before start for good snow driving came in use. It was dark, heavy snowfall and much snow covering the pavement and a very curvy road, ideal winter racing conditions! We had learnt a special 180° curve–technic, especially useful when going downhill. I will try to explain: Approaching a left hairpin driving on the right side of the road, I turned the wheel sharply to the left, blocked the breaks and then turned the steering-wheel completely to the right with blocked wheels. This made the car to skid more or less sideways into the curve with its back still swinging around. Once in the bend with the front pointing more or less in the right direction, breaks off and full throttle on 1st or 2nd gear. Still skidding we then accelerated out of the curve in the opposite direction. The procedure could be done with good control thanks to our steering-chains on the front wheels. But it was only possible to make this manoeuvre when we were alone in the hairpin bend, very often, however, that night, there was one or several cars stuck in the snow in the bend.

From Valence we climbed up to Gap were we joined the Route Napoléon. At my turn at the wheel, daylight came and it was snowing less, but still plenty of it on the road. Somewhere after Digne an English driver refused us to pass, which was unusual, after several kilometres of horn-blowing and blinking lights, I took a chance. The road was cleared, but not to its full width, and the snow-wall was on the road and not on its side. I forced the car over it with the 2 left wheels, and managed to pass the other car in throwing snow high above us with the bumper. What we did not notice was that the little valve under the radiator was opened by the snow pressure, and our radiator was slowly being emptied. The thermometer climbed to boiling, but as we were short of time, and as the next stop in Grass was not far away, we agreed upon to take a chance that the motor would take it.

A few kilometres before the centre of perfumes, Grass, the snow was gone and a Mediterranean sun gave us hope. Our snow chains could not take the bare asphalt, and one after the other broke and disappeared.

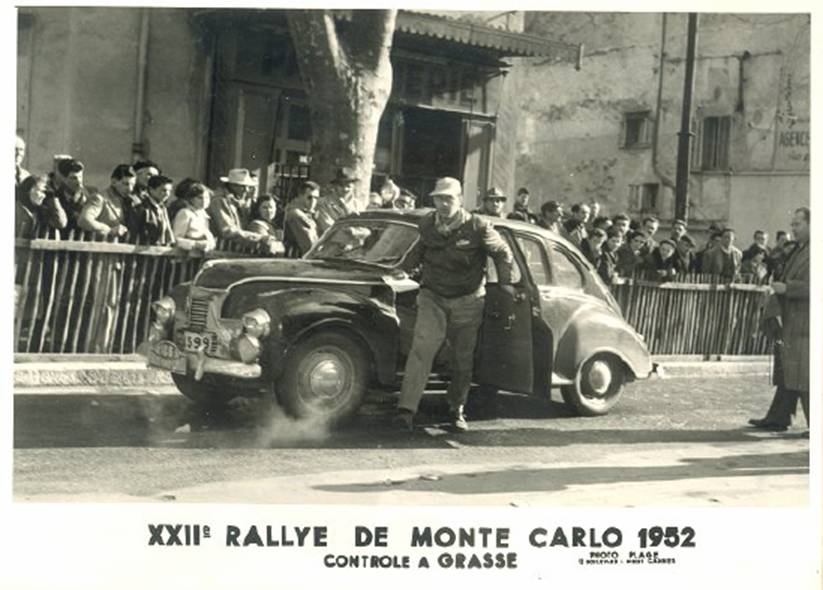

Then! - the most scaring seconds in my life came in the last downhill to Grass. We were speeding and braking intensely this last distance. In the final long narrow downhill, that ends up with a 180° bend just before the square, where the checkpoint was situated, our brakes failed due to overheating. The curve was full of spectators, children, balloons, grandmothers, etc… and there was no chance to get round that sharp curve at about 80 km/h (50 mi/h). I remember that I cried to Bosse “NO BRAKES”! Pulling the handbrake did not help much, but gearing down to the 2nd brought down our speed a little. We took that last curve on 2 screaming wheels, and all we saw of the public was their shoe-soles. Trembling and sweating we got out of our smoking car and had our road book stamped in time. Some people applauded as they thought that this was skilful and controlled driving! I can still see that bend and the people when closing my eyes.

Observe the smoke from the brakes.

When the brake drum gets overheated it changes its form due to expansion and becomes enlarged. The brake linings do then not contact the drum inner surface, with little or no braking efficiency. Once the drum has cooled off, it retakes its original shape, and the system works normally again.

After the car had cooled down a little, we continued to the first service station. There we filled water and changed the oil, or rather what was left of it. The oil-filter was completely silted up, and looked like it had been dipped in tar. Soot-flakes were floating on the oil, and it seemed as the heat had in one way or another carbonised the oil. Without doubt, the VW-oil cooler had saved our engine from collapse.

Driving along the Promenade Des Anglais in Nice in a very high mood, we were stopped by a polite policeman informing us that there was a speed-limit of 40 km/h (25 mi/h) to be respected.

And finally after some 70 hours of non-stop driving we arrived to the finishing line in Monte Carlo. As we came in among the first English cars it was obvious that we had done a good race, and people were applauding. According to the participation numbers, we had passed about 100 cars since Le Puy.

Our 3 Finnish friends that crashed outside Reims were waiting for us, still affected by Bacchus favourite products. “Are you still alive?” “Yes, Saint Peters has given us permission today” they answered happily.

The car had to be parked in a special area, and not to be touched until the final test. And all we needed were a shower and 20 hours sleep. The rally committee had reserved room for us and most drivers in the magnificent and old fashioned, Hôtel Beau Rivage.

Next day, Saturday the January 26, the inspection of the cars was done, and we passed without any comments.

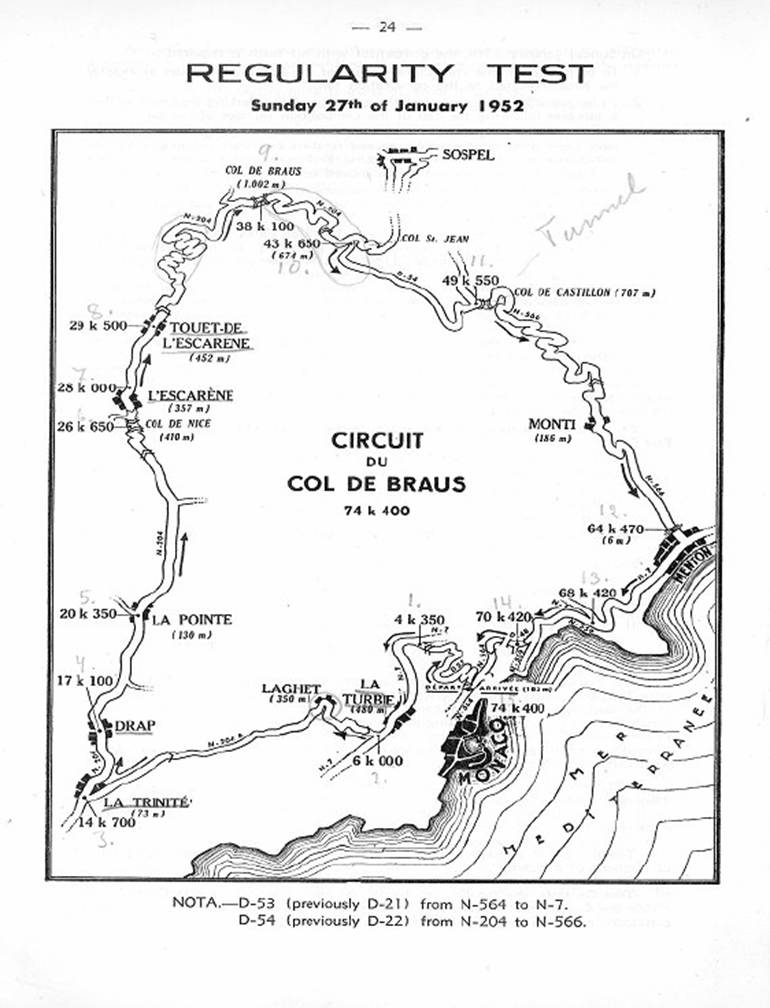

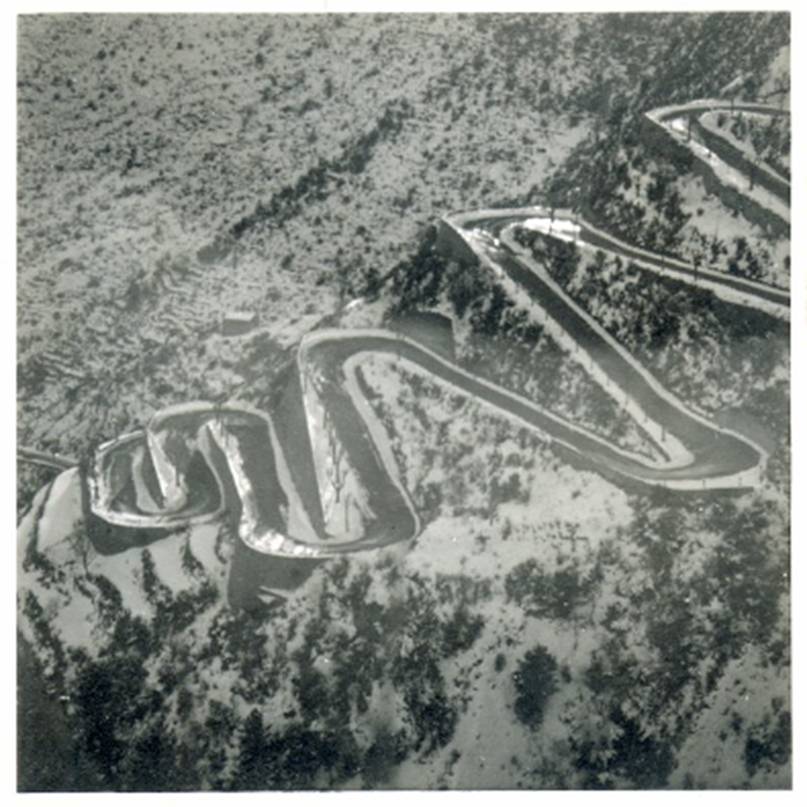

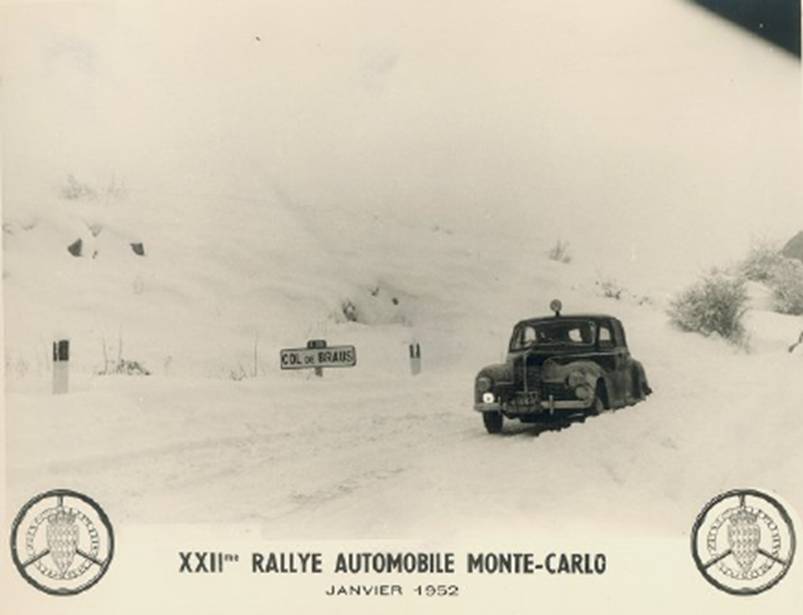

The final test was run on Sunday, on a 74.4 km (46.2 mi) circuit starting just above Monte Carlo and climbing up to a pass called Col de Braus at 1000 m (3280 ft) altitude. It had snowed again, and the palm trees were leaning under the unusual weight of snow on their leaves that morning, but rapidly the sun melted it. Also the road was free from snow except a little at the high altitudes.

All other traffic was stopped at this circuit. The 50 best cars participated in this final test.

Once again the average speed was set to 50 km/h (31 mi/h), but the 3 check points were secret. This increased considerably the difficulties, as practically a constant speed must be held. More than half the distance was, however, alpine roads, where 50 km/h was more or less impossible to respect. I should drive, and I must admit that I was very nervous before start, but once on the way and concentrating on the road, it was gone.

Bosse had his own time/velocity landmarks that we had worked out before start. But at some parts of the road it was impossible to keep the schedule. The whole circuit was done without any incidents, but at one spot we almost crashed. Going downhill after the “Col” the road was cut in a niche in the mountain side, and we were supposed to turn off to the right into a tunnel, which I did not observe in time. Anyway I made a sharp turn and the car skidded on the wet asphalt, but, maybe thanks to Saint Peter again, there was a dry spot just in the tunnel entrance. We did dust off the car against the tunnel wall, but no scratches.

The Col de Braus climb.

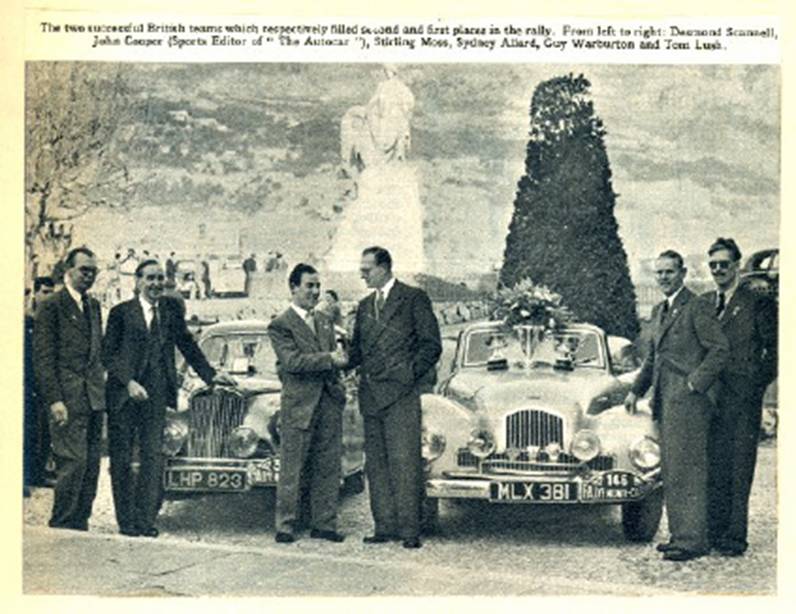

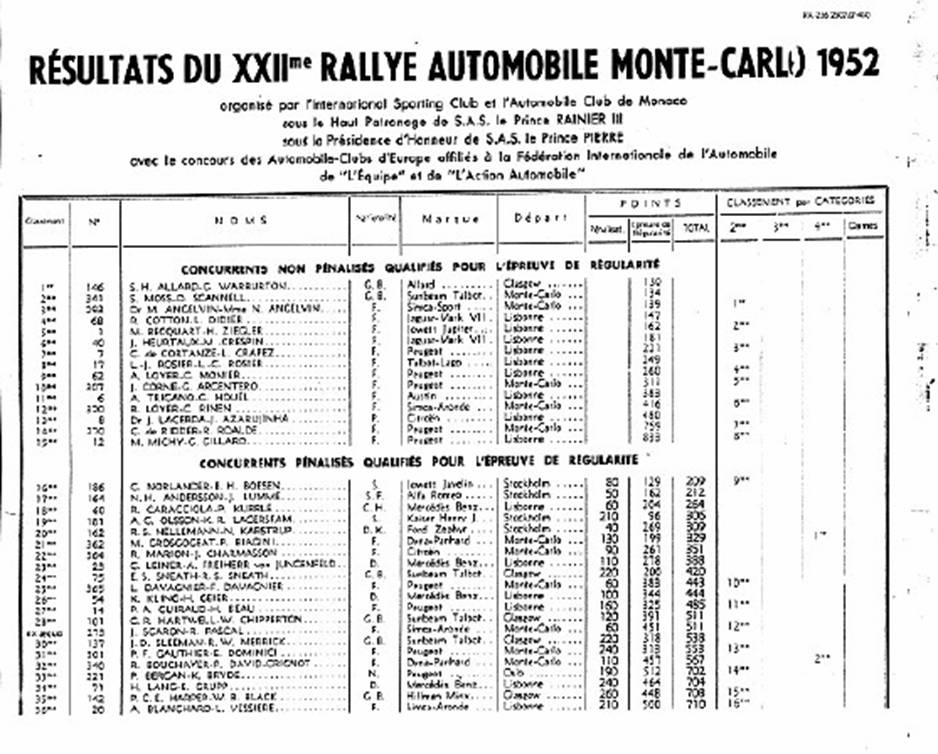

Later the same day the results of the Col de Braus test were announced, and we were second!!!! What joy and happiness. Our 129 (seconds) penalty points were only beaten by another Swedish driver, Gunnar Olsson that had 96 points,. He had an odd vehicle, a Henry J Kaiser car. Now the total results could be determined.

Drivers without any penalties were only 15, and the final test classified them in the order 1 to 15.. The over all winner was Sidney Allard in his own make of automobile with 130 points at the Col de Braus circuit. Second came Sterling Moss with 134 points in a Subeam Talbot. Very good English score!. The best Jowett Jupiter with No 1 on its rally plate was driven by a Frenchman, Bequart, who started in Lisbon and finished 5th with 162 points.

At the top.

We were 9th in our class, 1.5 L standard cars, and 16th totally. If it had not been for the 8 late minutes in Valence, and as we were 1 point better than Sidney Allard in the final test, we would have won the whole thing, but such is life! The final test winner, Gunnar Olsson had 21 minutes delay on his way to Monte Carlo and was placed 19th .

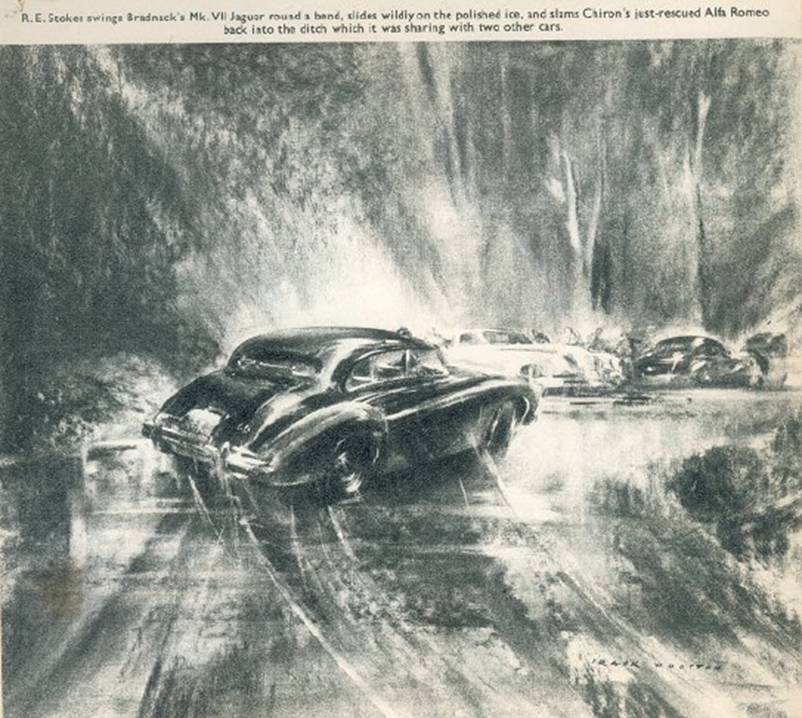

About 350 cars started this 22nd Monte Carlo Rally 1952. 163 crossed the finishing line, but out of those were 39 disqualified due to exceeding the 2 hours delay or other reasons. Most penalties were collected between Le Puy and Valence, due to that several roads were not trafficable in that area. An interesting observation is that 14, out of the 15 drivers without penalty, started in Lisbon or Monte Carlo, and as they were first in the rally order, they had the chance to pass this part before the heavy snowfall, that caused road blockades. The only penalty free driver coming from the North was Sidney Allard, who made a fantastic rally. From a newspaper I learnt that 6 persons were killed, but I do not know if this is true.

A Proud moment, the arrival in Monte Carlo, January 25th, 1952.

A number of more or less professionals participated, but Mercedes Benz showed for the first time what a professional rally-team is. They started in Lisbon with 3 cars, I have forgotten the model number, all white, and the drivers were the pre war Autounion F1 aces, Caracciola, Kling and Lang. In each checkpoint, there was a white van or rather lorry, with servicemen in white overalls decorated on the back with the 3-pointed star, waiting for them. I believe that Mercedes must have had at least 2 of these lorries following the rally. They finished 18th, 26th and 34th. The most famous French driver was Louis Gironde that went off the road with his Alfa Romeo. It was fantastic, that once in a life time, be able to beat all those famous drivers, including Sterling Moss in the final test.

On Monday there was the Comfort Competition, nothing for us. The day ended with the big Ball for All Rally Competitors. The last day, Tuesday the 29th, a parade was organised that ended up at the castle court, where the Prince of Monaco distributed the prices. Our placements 9th in the class and 16th totally and 2nd in the final test were not qualifying for any price, but we were very satisfied, as these results were much better than we ever expected.

One important thing we learnt from this rally, was that the seats must be comfortable, as after many hours, pains in the back occurs due to reduced blood circulation. Also it is of outmost importance that the co-driver gets a rest as often as possible. To solve these problems before the next Midnight Sun Rally in Sweden, we bought, when passing Paris on our way home, a couple of Citroen 2CV front-seat chairs. Those chairs was made by steel tubes, and seat and back was just rubber bands, about 1” wide, the back could be folded and thus the seat became a short bed. They were very light, and served from there on at all rallies.

For the next rally we installed safety belts, anchored in the floor behind each seat. No-one had ever seen that before in an automobile, 1952 !

Above: Göran (26) and Bosse (33), 1952.

Below: Göran (76) and Bosse (83), 2002

Cover page of “Motor” Jan.1952.

Jowett Javelin publicity

* * *